July 31, 2025 – Reviving 80-year-old fungal pathogens from a museum collection and comparing them with current strains reveals how decades of pesticide use and intensive farming have altered the invisible ecosystems that support global food production.

The new study, published in iScience—led by Dr. Dagan Sade under the supervision of Professor Gila Kahila from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s (HU) Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food, and Environment, in collaboration with other colleagues from HU, Tel Aviv University, Ben-Gurion University, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development—garnered critical insights into the evolution of fungicide resistance, environmental adaptation, and plant disease dynamics, paving the way for more sustainable, informed strategies in modern agriculture.

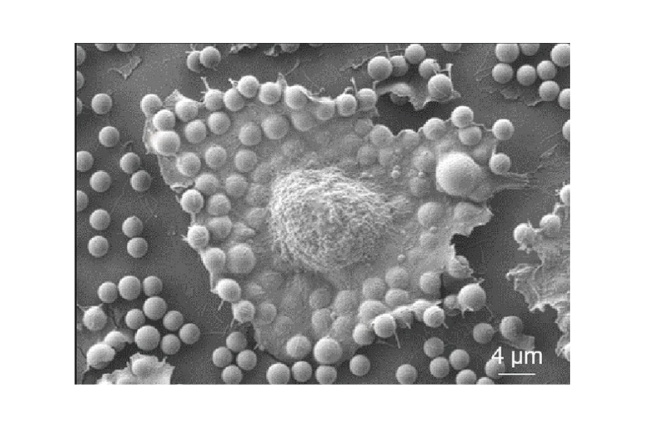

The researchers focused on Botrytis cinerea, a widespread plant pathogen responsible for gray mold disease in over 200 crop species. This fungus poses a significant threat to agriculture, resulting in billions of dollars in annual losses and presenting challenges to food security, trade, and environmental health. It was curated at the National Natural History Collection of Hebrew University since the early 1940s, decades before modern agrochemicals became standard in farming. These historical specimens were carefully reanimated and subjected to cutting-edge analyses, including whole-genome sequencing, transcriptomics (gene expression profiling), and metabolomics (chemical fingerprinting).

The findings were striking: the historical strains showed significant genetic and behavioral differences compared to modern lab strains of the same fungus. In particular, they revealed:

Reduced signs of fungicide resistance, a feature that has become prominent in modern strains due to heavy chemical use.

Differences in pathogenicity, with some traits suggesting the historical fungi were less specialized and aggressive than their contemporary counterparts.

Adaptations to different environmental conditions, including pH tolerance and host specificity.

“These fungi have been quietly evolving in response to everything we’ve done in agriculture over the past 80 years,” said the researchers. “By comparing ancient and modern strains, we can measure the biological cost of human intervention—and learn how to do better.”

This research has wide-ranging implications. In the era of climate change, pesticide overuse, and declining soil health, understanding how plant pathogens adapt to human activity is key to developing sustainable farming systems. Reviving historical microorganisms provides a baseline for this understanding—a way to distinguish between natural evolutionary changes and those driven by anthropogenic pressures.

The study also contributes to global efforts to predict and manage plant disease outbreaks. By revealing how pathogens adapted to previous environmental shifts, scientists can better model future risks and design resilient crop protection strategies, potentially reducing reliance on chemical treatments that harm ecosystems and accelerate resistance.

The research paper titled “From Herbarium to life: Implications of Reviving Historical Fungi for Modern Plant Pathology and Agriculture,” published in iScience, can be accessed here.

Researchers:

Dagan Sade1,2, Gilli Breuer3, Ksenia Juravel2, Weronika Jasinska5, Aviel Arzi11, Nir Sade4, Yariv Brotman4, Yael Meller Harel6, Shay Covo3, Maggie Levy3 and Gila Kahila Bar-Gal1,2

Institutions:

- The wildlife CryoBank, The National Natural History Collections of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, The Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, The Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- School of Plant Sciences and Food Security, Tel Aviv University

- Department of Life Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

- Division for Plant Pests and Diseases, Plant Protection and Inspection Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Bet Dagan